This month is Autism Awareness Month across the world. Here, Paul Wheeler tells the very personal tale of how the world of women’s football and more particularly working with the staff and players of Coventry United Women has helped him find a safe place and make his daily struggles living as a high-functioning autistic person in an often confusing world a little easier, often without realising they’re doing so.

“I used to say that I thought I needed space to find my balance. But I might need a hand, so if you could be that, I might need some help to find my balance”

Lucy Spraggan: ‘Balance’

This post is unusual for an Since 71 post, in that almost none of it will deal with women’s football. At least not the action on the pitch, anyway. It also starts with a confession.

This is a confession that up until now I’ve not really made to many people, and one that will make you question why and how on earth I’ve ended up in a position where I talk to people about football most days, whether it be live on air commentating on women’s football for the FA Player or for Coventry United, or interviewing players and managers, or even appearing on the odd women’s football podcast that’s watched and listened to by a decent number of people, or talking about women’s football on social media. It might be seen as proof I’ve been lying to pretty much everyone in plain sight and getting away with it the whole time I’ve been involved in women’s football. Or at least misleading them. So here it is.

That confession is that I’m absolutely terrified of talking to people the first few times I meet them and even when I know people incredibly well, I’m still unsure, to the point that there is a good chance anyone who’s ever interacted with me in women’s football has only seen a performance, not the real me, and has definitely seen at least one occasion where it might not sound like it but inside I am practically screaming with terror and a large chunk of my brain is worried that my real self is going to get found out every minute.

I should point out that when I say “terrified” “oh I don’t fancy that” terrified or “oh, that seems tricky” terrified. I’m talking cold-sweats-in-the-night terrified. Have-to-follow-a-routine-to-psyche-yourself-up-every-single-time terrified. “Oh-god-they-must-think-I’m-so-stupid” terrified. Often-feel-absolutely-physically-worn-out or have-to-sit-quietly-in-a-safe-place terrified.

I’ve learned to hide it well over the years. It’s something we autistic people learn almost without realising. It’s like performing a role or putting on a mask – in fact, it even has the name “masking”. Masking in autistic people is defined as “learning, practising, and performing certain behaviours and suppressing others in order to be more like the people around them”.

The best way I can describe why I struggle in social situations and particularly things like interviews as an autistic person is – imagine you’re trying to have a conversation with someone. In a neurotypical person, your brain is probably concentrating fully on the person in front of you. You’re listening to the conversation and without even realising it you’re picking up on body language, tone and all the other things but they’re not necessarily registering with you and you’re not having to (or being forced to) consciously acknowledge them. This is basically what happens in every social interaction.

Now imagine you’re trying to do that, but at the same time, you can hear a muffled conversation on the other side of the room. Are they talking about something you should know? There’s a shout outside – was it someone shouting at you? That fluorescent light is buzzing too – someone should probably fix that.

That dog’s barking again and the people across the room have just mentioned dinner which reminds you, what should you have for dinner this evening cause the fridge is empty and hold on you’ve been looking at the person you’re talking to without blinking for too long so blink before they feel unsettled but also you need to check the recording is working because you’ve only got one chance at this and what if your next question makes them think you’re stupid and that light is STILL buzzing and the other person has just raised a point you want them to elaborate on and there’s a police siren outside that’s REALLY LOUD and oh no you’re running long on time and they probably need to go soon to get back to what they were doing and by the way you need to work out how to respond to this answer and keep the conversation going and there might be loads of other people waiting and WHY IS THAT LIGHT STILL BUZZING and oh wait they’ve finished talking next question what was I going to ask oh yeah god I wish I’d asked that better but oh well…

That was exhausting to read, wasn’t it? Now imagine that is every social interaction. Every day. And by the way, some of these you have to fire off because other people will listen to them!

But if you look at me, you wouldn’t know any of this is happening – you’d see someone having a conversation and (hopefully) producing a great, knowledgeable interview/discussion or even just a basic conversation. That is what masking is. It’s like a duck paddling under the surface. It’s what being autistic is. Unless you are a neurodiverse person, you can’t fully understand it.

Sports commentary, too, is something I love doing and I’m truly proud to do. But here, too, being autistic has an indelible approach on how I face a game.

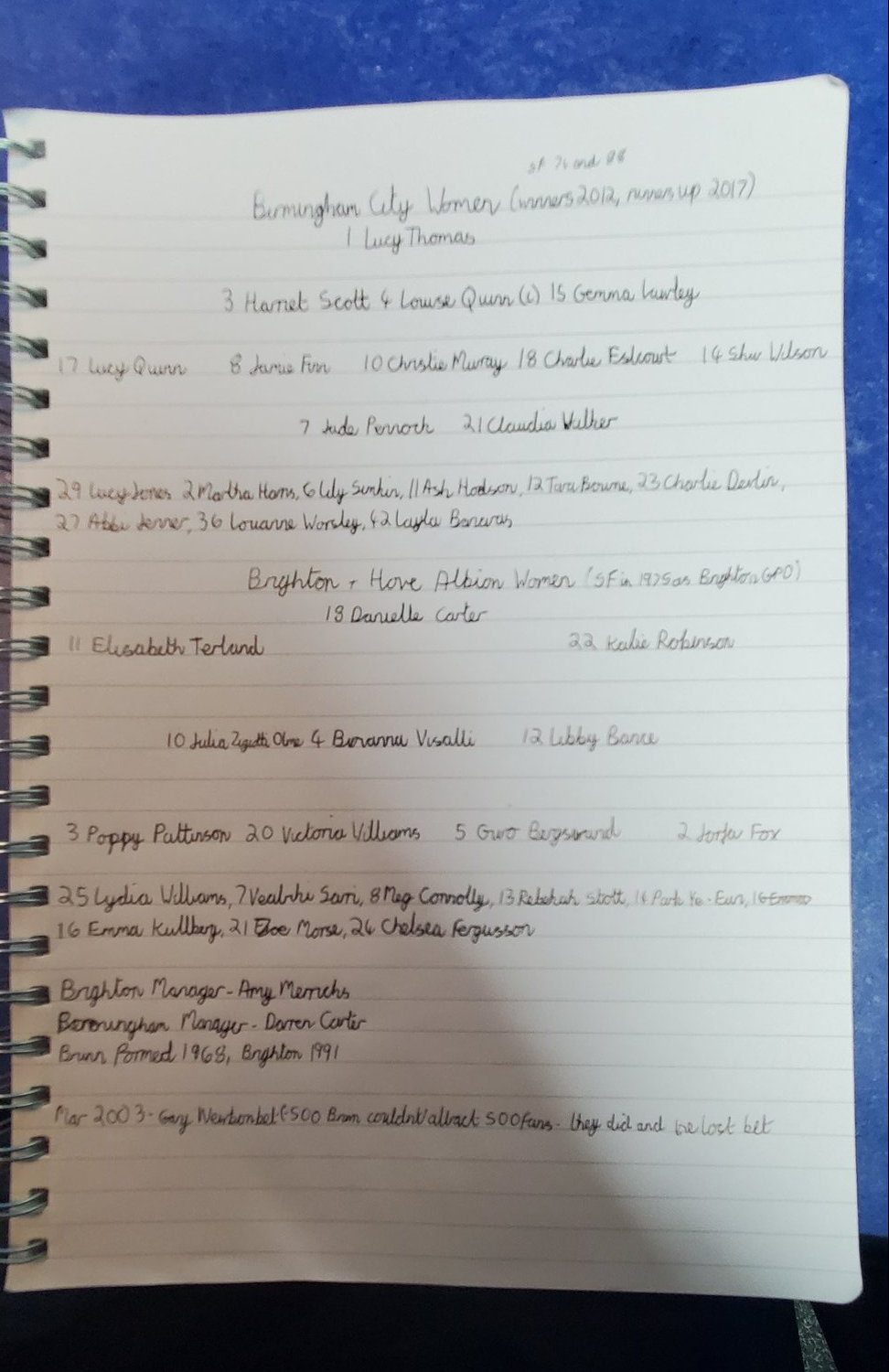

Because of the way my brain works, I have to approach it like someone else might approach actually playing a game. Loud, driving music while on the way to the ground (I’m a metalhead, so that makes life easier) that blocks out the rest of the world and drowns out the million other voices in my head. Every match set up the same way and the tech tested and ready with plenty of time to go. Although I prepare for games to within an inch of my life, the actual notes I run off on game days are the two teams written out in their likely formations, maybe a few chicken-scratch scrawls around key facts-and that’s it. Not for me the intricate notes systems of some others – anything over-complicated or too much information in front of me and my brain screams for mercy and begins to shut down through over-stimulation.

That’s not all, though. While most folks are fairly quiet and focused before games I’m a full-on ball of energy – I’ve had funny looks once or twice when five minutes before kickoff in the pressbox I’m literally shaking in my seat with energy – that’s my body’s response to the dopamine rush that is what my autistic brain craves in order to function “normally”.

And then there’s the game itself. I’ve been told I see the game “differently” to many commentators – the best way I can describe it is that whilst watching football I am aware of EVERYTHING – the noise in the crowd, the movements of the players off the ball, even the feel of the wind – to a level which physically makes me almost shake in the commentary box. My brain is constantly watching two or three moves ahead and anticipating what’s coming as well as trying to keep things calm on air and react to the game in front of me…which is a wonderful experience but also physically tiring. I’m the same watching games – I tried to convey the experience in my story of attending the Euros 2022 final – but this passage, here, best explains how I watch football. This is an autistic experience of Chloe Kelly’s Euros winning goal, with everything I saw and heard and felt all at once.

I remember the corner being won, and looking up at the screen as Felicitas Rauch jogged back into her position after conceding it.

I remember watching Millie Bright line up for another charge into the mixer and wondering if this was the one she got on the end of. I remember, as the white and green shirts jostled, and the crowd roared, and the heat hung over Wembley, and the sweat dripped into my eyes, and someone nearby yelled “THIS TIME, GIRLS!” and Lauren Hemp walked over to take the kick and Lucy Bronze appeared on the big screen adjusting her headband like a ritual with eyes full of fire staring into a future only she could see, looking up and seeing the arch, like a rainbow bridge over this football Valhalla, as spots of rain threatened to fall.

And I remember praying, like I only ever have once before at a football match as Mollie Green stepped up to take a free kick heard around the world for Coventry United. I used the same words then, too. “Please. Whatever is up there. Listen”. And then I remember the thump of Hemp’s left boot, and the ball arcing small and white against the massed colours of the crowd behind it, and Lucy Bronze flying from nowhere, and the ball ricocheting, and rising to my feet with 87,000 others, and holding my breath, and the small, blonde figure of Chloe Kelly swinging her leg and somehow not falling, and Merle Frohms frozen, and time slowing down as Kelly jabbed out her right leg, lunging, reaching. I remember seeing the ball roll oh so slowly over the line. And then, I remember nothing except the noise.

Even as Chloe Kelly raced away, and the world saw her spin her jersey like she would take off and fly underneath it, and my partner yelled “She’s taken her shirt off” still, the overwhelming memory is not the sights, but the sound. It rolled like an avalanche over Wembley. It was the audio equivalent of a whiteout. A scream of victory so primal and joyful that if you bottled it, you could conquer worlds. Unlike us mere mortals, it did not care about goalkeeping criticisms, or discussions about positioning, or even VAR. It just was.

Basically, what I’m trying to tell you is that football, for me, is an incredibly intense experience, which is often a benefit for commentating but is sometimes hard to understand. When you combine that with the fact that while doing interviews I either can’t make eye contact at all or have to hyperfocus.

I also speak pretty quietly and am physically awkward (very weirdly for someone who plays ice hockey for fun), and I’ll often turn up at games wearing metal-band hoodies and looking more like I’m heading for a mosh pit than a football commentary because these are the clothes I feel most comfortable and least self-conscious out in public in) – would you expect this to be the normal image of a football commentator at a game?

Can you imagine how this outfit would go down in a Premier League or even a WSL press box?

Despite all that, and with all the barriers in the way, the Butts Park Arena and Coventry United has become one of the rare places I feel totally accepted as myself.

And a HUGE amount of that is to do with the people – whether it be the media officer Connor West and who first decided he was going to let a slightly awkward-looking bloke into the Butts Park Arena press box, photographer Jeff Bennett for the gameday laughs, past and present coaching teams (Jay Bradford and Jo Potter last season, and Lee Burch, Sian Osmond & Mikey Emery this) who have been generous with their time, expertise and level of access granted to the point I am a regular face at almost every training session and routinely travel with the team to away games), the off-field management staff like GM Jack Heaselden who is always approachable – and most importantly the players, who put up with this slightly-awkward thirty-something asking them questions every week and have accepted me almost as one of the team staff. Players like Anna Wilcox, Liv Fergusson and Katy Morris last season, and Jodie Bartle and Merrick Will this who have happily and willingly broken down the sometimes-invisible barriers that exist between elite athletes and those who cover them and made interviewing and talking to them a joy even for someone like me who’s terrified of talking to people.

There has been a lot of talk of how the Lionesses have become role models and changed the game, but perhaps less of how women’s football can be a force for change without even really realising it. The staff and players of Coventry United probably don’t realise the effect covering them and their response to it has had upon me over the past few seasons, but for an autistic person like me who has struggled to feel accepted or even comfortable and doesn’t trust easily, their actions have been part of driving an immeasurable change in me. Because of them, I’m far more confident. Because of them, someone who’s always struggled with self-esteem and a chance to be taken seriously in the world of sports has become more able to follow their dream.

And perhaps most importantly, their work and the work I’ve done with Coventry United has led to further opportunities, including the change to commentate on elite football for the FA Player.

This is particularly important to me. After 30 years and more of struggle to find who I was and often feeling excluded from a large part of society – a struggle that directly led to mental health issues that I’ve only relatively recently overcome – I’m getting the chance to follow a dream I’ve had since I’ve been a child…one that at times I never thought I’d be able to reach.

As a proud member of the neurodiverse community, I’m aware of the struggles people like me face to be taken seriously in society and have lived them myself – if you want an example of the way football and society as a whole views autistic people then look at the abuse and responses on social media to Wigan Athletic’s James McClean openly saying he, too is autistic. Women’s football has largely been different so far (I am particularly put in mind of the way “big” women’s football journos like Tom Garry and Kathryn Batte, for example, have been generous in their support and welcome too, which I am always grateful for) but when you go into every professional space in a state born from experience of being braced for trouble and the odd sneering word, being wholeheartedly welcomed helps a lot.

I am unaware of any other openly autistic football commentators, for example, and it makes me immensely proud that I can represent an often-misunderstood group commentating for the FA and show the world how talented we can be and what we can offer, and I couldn’t do that without the way Coventry United have made me feel comfortable to be my “true” self and not be ashamed of who I am.

The quiet moments I treasure from my work covering football: Coventry United train at sunset on a winter’s evening as a train rumbles past the Butts Park Arena

This week, leading into April is the start of Autism Awareness month – a month that tries to show the skills and benefits that autistic people – a group who are disproportionately disadvantaged when it comes to access to work (only one in five autistic people are in any sort of employment, for example) and often stigmatised by society can bring to the world. Football, like anywhere else, can benefit from our presence, whether as players, coaches or commentators, and without realising it the players and staff of Coventry United are playing a key role in helping that happen just by recognising that talent and giving it a chance to be unapologetically itself around them in my case.

Living as an autistic person is often a battle to fit in in a world where everyone else seems to know the rules and you’ve never been told them.

There is a lot more to be done for us to be truly accepted by parts of society and be given the same chances as neurotypical people – the comments about James McClean from football fans show that, and as I’ve said I’m unaware of another (openly) autistic commentator or indeed journalist in football at any “elite” level.

But whilst they’re not perfect, at least the team are showing a willingness to try and make that battle easier. And in the process, they’re playing a part in improving the lot and opportunities for at least one autistic person to thrive.

And for that this Autism Awareness Month, I thank every single player and staff member for helping make the world a better, more welcoming place and giving me somewhere I can truly be myself and not have to fight against my own brain just to fit in.

It will forever mean that this club and the people I’ve come into contact with around it mean more to me than I can ever really put into words, from the utterly incredible rollercoaster that was the Great Escape to sharing the few highs and many lows of having to start from scratch again this season. It’s a journey I hope I can continue to go on, and that more autistic people are given the chance to go upon with their own football clubs at any level-football clubs need to realise that if they give us autistics a chance, they’ll get so much back in return.

Happy Autism Awareness Month.